The Challenge of Reopening College Campuses

April 14, 2020

legal services law students covid-19 law education higher ed

Perhaps by Memorial Day, college presidents and their leadership teams will face what will likely be the most important decision of their collective tenures: when to open the dormitories and classrooms on their campuses following the COVID-19 crisis. Even though we are bombarded with new information each day, it is safe to predict that these decisions will be made with at best imperfect information. And even with massive testing and effective treatment, COVID-19 will continue to present a threat to campuses until there is widespread immunity that occurs naturally or from a vaccine.

Higher education leaders are considering these issues now. Even though no two campuses are the same, no university wants to go at it alone, especially because there will be nothing more chaotic than similarly situated institutions making different determinations. When decisions are announced, they will be announced at roughly the same time. Every single college will preface the announcement with a statement that no principle is more important than the safety of students, faculty, staff, and administrators. But within the context of our legal system, what does that really mean?

At the outset, there will have to be some (and perhaps extraordinary) risk tolerance. No matter what decision is made, there will be litigation—with claims from parents who want partial or full tuition refunds (several class actions already have been filed) or from students who become physically or emotionally ill on campus. In this regard there are some obvious rules that the chief legal officer on each campus must follow. One is to be involved in the decision–making process. No decision should be made without a careful consideration of all of the legal risks, which includes the risk from defaulting on obligations in contracts the school may have. Colleges could be entering one of the most litigious periods in their history. Second, don’t make the mistake of having your usual litigation firms conduct the analysis of what constitutes “compliance” with the standard of care on your campus. Whoever does that work is likely to be a witness in litigation.

But back to the question that I posed above: what does safety really mean?

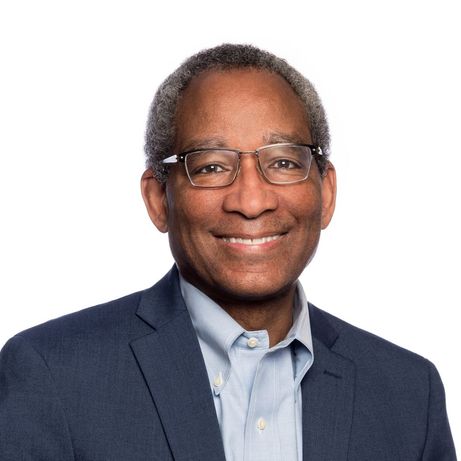

I spent thirty years as a trustee and general counsel of a leading research university. (Before that, I spent seven years as a student on two college campuses.) As a trustee, I spent over 20 years as a chair and member of the committee responsible for the oversight of student life. What I learned from that experience is that up to this point, the student experience on campus has been about everything other than social distancing. Students are forced to be in a crowd—whether in class, theater, musical performances, intercollegiate/intramural/club sports, the dining hall, and dorms. And whether it is on or off-campus, there are weekly parties that often take place in crowded spaces and without the kind of sanitary practices that are being demanded now.

If college administrators, acting on the advice of health and environmental safety experts, can design an effective process for social distancing on campus, the first hurdle is how such rules are enforced. But for the sake of this discussion, assume that administrators can be successful in implementing a social distancing plan that will change in a matter of weeks the nature of engagement for decades on college campuses.

The issue that should come to mind is whether students will be happy in this new environment. Stated otherwise, what will the impact be on their mental health? Administrators will have to decide whether the activities outside of the classroom that have been said to drive student satisfaction, but might now be put on hold (or eliminated altogether), are necessary to the students’ emotional well– being. Further, they must rethink the value that is implicitly expected as part of the room and board experience—for which, of course, students are paying.

As they address that issue, the second question will be what safety precautions need to be taken in order to comply with the standard of care. There has been, and will be, a variety of standards and opinions on best practices. The standards are likely to be issued in the form of guidance, which means that administrators will have to decide which ones best fit their campus profile. This reminds me of my 30 years as a tort and product liability trial attorney: evidence of the standard of care might meet a preliminary burden, but it generally is not conclusive. Thus, it is inevitable that even the most careful and thorough process will leave colleges open to risk. The best way to deal with risks is to prepare for them—engaging as necessary with skilled professionals who know what you are dealing with.

The list of practices that might lead to the reopening of campuses and dormitories includes the following:

- Students required to produce negative test results before coming to campus.

- Students required to take daily (weekly?) temperature checks.

- Students required to wear face masks on campus.

- Class sizes reduced and class times staggered so that the flow of students and faculty in and out of classrooms will create less traffic.

- Study abroad programs eliminated.

- International students not allowed to travel home during the academic year.

- Strict limitations on the size of gatherings on campus.

- No intramural or club sports or pickup games (or students participate only after signing releases—take a look at whether those releases can be enforced).

- A reconfiguration of dormitory space so as to enable social distancing (consider the limitations in terms of facilities and the economic impact).

- A reconfiguration of dining hall space or staggered schedules so as to enable social distancing (consider limitations and economic impact).

- A reconfiguration of lecture halls and classrooms to enable social distancing.

- The elimination of service in dining halls; dining halls provide take out services only, giving students the capacity to order online.

- An enhanced schedule of cleaning and disinfecting of dorm rooms (don’t rely on students to do this) as well as all common areas on campus.

- Stagger the return of students to campus, beginning with students for whom online education does not work—for example, students who need access to labs.

- Create a hybrid of live and online classes, perhaps with students whose id’s end in even numbers attending live on one day, while those ending in odd attending on another.

These are only some of the possibilities. Taken individually or as a whole, what will be the impact of these new practices on the quality of the student experience, student satisfaction, and student health? The demand for psychological services on campus, which has increased dramatically in the last decade, is likely to become even stronger. And what about the strain on the service providers?

The nature of the challenge here is clear. Although testing can, in theory, be mandated, social distancing is highly dependent on voluntary compliance. And even a robust testing protocol will not ensure the absence of new exposures because students (and others) cannot be contained on campuses. It seems unlikely that colleges are going to track the movement of students on and off-campus. And, of course, the students are far from the only source of infection on campuses. There are professors and visiting scholars, staff members and their families, administrators and their families, contractors, and visitors from other campuses. Indeed, the freedom to move on and off of campuses has been a key feature of higher education in this country.

There are so many other issues that will arise depending on the decisions that colleges make, and so many additional changes to come. For example, will insurance companies create a new form of insurance that schools can purchase to offset some of the risks of re-opening before things are totally settled? Are there actions colleges can take to stave off the litigation that has already started?

In addition to the issues addressed here, there are other legal issues that might arise if a campus employee contracts COVID-19 in the work environment.

Feel free to reach out to me to discuss any of these ideas further. While these are truly uncertain times, informed collaboration and experience will navigate your campus through them successfully.

Back to Expertise